The enormity of Andy Murray’s win at Wimbledon last Sunday still hasn’t quite sunk in across our nation.

Continue reading “Pensions – Two sets down, can we come back?”

The blog of Robert Gardner, co-CEO of Redington

The enormity of Andy Murray’s win at Wimbledon last Sunday still hasn’t quite sunk in across our nation.

Continue reading “Pensions – Two sets down, can we come back?”

Pension funds face an eternally difficult process of setting goals and then making sure they reach them. It doesn’t sound complicated, but it is.

Continue reading “Are you SMART? How pension funds can set the right kinds of goals.”

HM Government are urging pension funds and insurers to increase their investment in UK infrastructure and housing. See Match.com? Making the pensions and infrastructure romance work. But what do these asset classes offer pension funds and insurance companies and do the potential rewards really justify the additional governance and risk?

Continue reading “Are you interested in investing in Infrastructure, Social Housing and Property?”

Denver, Colorado.

On Wednesday 6th March I was at Heathrow boarding a flight as many other pensions people were; but the flight was not to Edinburgh for the annual investment conference. Instead, I flew to Denver, the mile high city and capital of Colorado state.

Continue reading “Which city is a mile high and the state pension invests in infrastructure?”

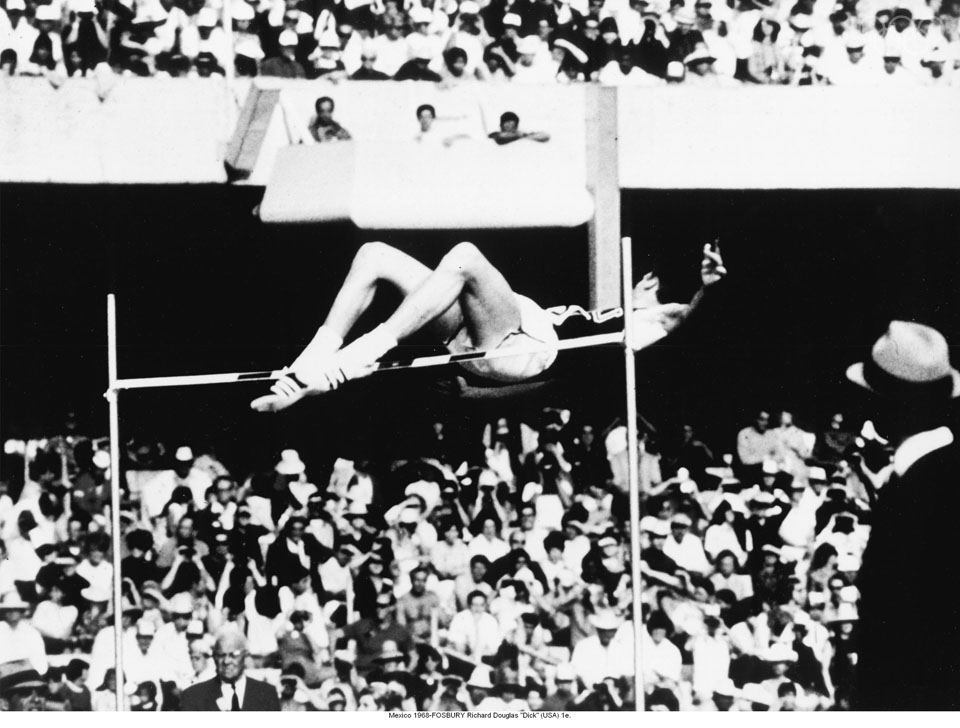

Dick Fosbury commented on the High Jump Final in Mexico 1968 “I guess it did look kind of weird at first,” he said, “but it felt so natural that, like all good ideas, you just wonder why no one had thought of it before me.”

Dick Fosbury commented on the High Jump Final in Mexico 1968 “I guess it did look kind of weird at first,” he said, “but it felt so natural that, like all good ideas, you just wonder why no one had thought of it before me.”

Liability Driven Investing “LDI” is to pension fund asset allocation and risk management what the “Fosbury Flop” is to High Jump. Mexico Olympics 1968: Richard Douglas “Dick” Fosbury (born March 6, 1947) introduced a revolutionary approach to High Jump which resulted in his winning a Gold Medal and setting a new Olympic Record at 2.24 meters (7 feet 4.25 inches). His then new and unique “back-first” technique, now known as the Fosbury Flop, is adopted by almost all high jumpers today. During the 1960s there were several high jump techniques, the scissor kick, western roll and the straddle, but Fosbury’s technique was to sprint diagonally towards the bar, then curve and leap backwards over it. The standing Olympic record before Fosbury introduced his Flop was 2.18m, held by Valeriy Brumel, who used the straight-leg straddle technique to win the Tokyo 1964 Olympics.

As a young boy, Dick Fosbury was taught both the western roll and the scissors style. In a 2008 interview with Simon Burnton of the Guardian, he said “In the very next meet, as I was attempting a new personal best, I felt I had to do something different to clear the bar and I tried lifting my hips, which caused my shoulders to go back, and I succeeded. I made a new height, I tried again, and successively I was able to clear six inches higher than my previous best, and that change made me competitive, it kept me in the game, and I converted from sitting on the bar to laying flat on my back.”

In 1965 he got a scholarship to Oregon State University where he continued to work with his coach Berny Wagner. But Wagner was no fan of the flop, which he considered “a shortcut to mediocrity”. However, one day in the summer of 1966, Wagner decided to capture the flop on video for posterity. He set the bar at 6ft 6in, and filmed Fosbury sailing over it. Reviewing the footage, he realised that his pupil had cleared the bar by a good six inches. “That,” he said, “was when I first thought he was going to be a high jumper.” But Fosbury was still a long way from being an Olympic champion. By 1967 he had risen to a world ranking of 61, but even by the time of the Olympic trials, held a month before the Games began, he was not considered a likely medallist.

At the Mexico 1968 Olympic Games high jump final the bar started at 2m (6ft 6in). With his revolutionary technique, Fosbury had made four successive jumps easily sailing over the bar at 2.18m. From 61st in the world going in, he was now guaranteed a medal alongside his fellow American Ed Caruthers, and the Soviet Valentin Gavrilov. The fifth high jump at 2.20m was cleared by all three athletes, but on the sixth jump, Gavrilov failed at 2.22m.This left Fosbury and Caruthers fighting for gold. Fosbury had not missed a single jump in the competition, though, whilst Caruthers had failed five times. The sixth high jump bar was then set at 2.24m (7ft 4in), a new Olympic record height. Fosbury with his longer run-up and lengthier preparation sailed over the 2.24m bar. But Caruthers failed in his attempt. History was made when Dick Fosbury became Olympic Gold Medallist with a revolutionary new and superior approach to high jump.

Fosbury’s innovation, though, was not immediately embraced by high jump athletes. Four years later, in the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, twenty eight of the forty competitors used Fosbury’s technique, but Juri Tarmak of the Soviet Union won Gold using the straddle technique. Since then, though, all Olympic medals in this discipline have been won using the Fosbury Flop. Today it is by far the most popular technique in modern high jumping.

Mexico 1968 high Jump Final (Fosbury 2.24m Ed charuters 2.22m).

Why? There were several high-jump techniques: scissors, western roll and straddle. All attacked the bar from the side or face on and all use the inner foot to take off. Conversely, in the Fosbury flop, the athlete runs up in a curve, jumps by taking off from their outer foot and twists their body to clear the bar with their back. They finish the movement by lifting their legs over the bar and landing on a mattress. The back-first jump offers many improvements compared to traditional techniques: the curved run-up allows the high-jumper to reach the bar with more speed and to do a more powerful jump. The body arches over the bar and the centre of gravity is underneath, which is an indisputable mechanical advantage. In just one Olympic Games, Dick Fosbury excelled by revolutionising the high jump discipline, making his mark on both the history of athletics and the entire future of the sport.

Friends Provident swaps away pensions risk

On the 3rd December 2003 the Friends Provident Pension Fund made history by implementing a brand new technique to manage the long-term health of the Fund. The UK life assurance company implemented derivatives to hedge out its pension fund liabilities against interest rate and inflation risk.

Following the analysis by Dawid Konotey-Ahulu and the Merrill Lynch RedAlpha team, Friends Provident designed and implemented a far more effective solution for ensuring the pension fund’s long-term strength than the cash flow or asset mixes that other companies were focusing on at the time. According to Graham Aslet, the Company Appointed Actuary, the question you should be asking yourself is not whether to use bonds, like Boots a few years earlier, or equity, like most pension funds, but how big your swap should be. Like Dick Fosbury, Graham Aslet and Friends Provident were looking for a revolutionary approach to achieve success. A year later Graham Aslet said in an interview “I don’t think we had previously considered that route because of the slight stigma that is still attached to the use of derivatives. The necessary hedging involved in life assurance is one thing, but having to convince naturally conservative trustees of their use and safety is another.”

Why would you voluntarily run £1 million a basis point of risk in your pension fund?

Although the technique was new for pension funds it was not new for corporates. Dawid Konotey-Ahulu, then Managing Director of the Merrill Lynch Insurance & Pensions Solutions Group, argued that, if a fund has the same status as a corporate bond, it is odd that companies are happy to run risks in their pension fund that they would never dream of running within the rest of the company. He said in a press interview “Almost every major issuer of international debt covers itself against currency and interest rate risk, taking out derivatives to switch its exposure from fixed to floating rates, but not one covers itself against pension fund risk”. That risk is derived from a pension fund’s real yield, which is determined by nominal interest rates and long-term inflation expectations. A good proxy for UK pension fund yields is the yield on the gilt, shown in the chart below. As it shows, the real yield on the 2035 index-linked gilt has fallen from 2.12% to 1.52% in the space of a year. If a company had a £500 million pension fund, that 60bp fall in real yield would result in a fall in the value of the fund of £60 million. It would be a disastrous equity market that produced that scale of damage for a fund in the space of a year.

Using Liability Driven Investing using swaps to hedge the liabilities, not equities or bonds, is the answer

Many companies had begun to recognise the problem. But their answer was either to concentrate on getting the maximum return from the equities that make up their pension fund, or to cashflow match using bonds to extend the income from their assets out to a predictable amount over 20 or 25 years. But equities were not the answer: the European markets had risen in 2003 and 2004, but despite that, pension fund deficits still relentlessly rose. Neither are longer-dated bonds the solution: the risk to a fund from real interest rates is at 60, 70 or 80 years in the future. Buying bonds that expire in 25 years will not help. At the time, the 30 year Index-Linked Gilt was the longest duration bond. UK retailer Boots is a good example of a company that bought bonds in order to try and cash-flow match, but reverted to equity when the bonds failed to solve its dilemma.

Chart showing the LDI swaps hedge mark-to-market valuve versus the Real Yield

Source: Merrill Lynch RedAlpha 2005

The reason for the rise in pension fund deficits despite improving equity markets in 2003 and 2004 was because the size of the liabilities had risen by more than the rise in equity markets. Furthermore, because most pension funds were underfunded, i.e. their assets were less than their liabilities, the real yield volatility impacted 100% of the liabilities which might be 25% greater than the asset value of the pension fund. Dawid commented at the time that “A lot of companies understand that interest rates and inflation are hurting the pension fund; what they don’t understand is the detail of how and where. They need a strategy to immunize the volatility in the liabilities: an asset whose value moves in the opposite direction to the liability and which they can tailor to match their specific sensitivities,”.

The use of swaps by pension funds was novel as, on day one, the swaps began with a value of zero. Their value then alters as inflation or interest rates change. The key for pension funds is to design a portfolio of swaps that mirrors the mark-to-market change in the value of the liabilities. Interestingly, this concept was known as duration matching, and was originally proposed by the Life Actuary Frank Redington in the mid 1950s. The only difference with this modern approach is that the duration matching tool was an interest rate swap and an inflation swap.

One reason many other pension funds at the time would not consider hedging using swaps was that they believed wholeheartedly real interest rates were as low as they were going to go. It was quite a risk to take, to try and call the market when you could be losing £1 million for every basis point the real yield falls. In an interview in 2004 Dawid said “A year ago lots of companies looked at the real yield at 2.15% and said it was at historic lows. One or two even took the view that it would be impossible for the real yield to fall below 2% and therefore decided not to hedge. But it fell to 1.9%, 1.7% and it’s now at 1.5%. Given that you really have to say there is a chance the real yield could fall a lot further”. What’s more, the nature of interest rate yield curves is that it is negatively convex: the lower the yield gets, the greater the proportionate cost of each basis point drop. A pension fund’s sensitivity may be £1 million a basis point now, but if interest rates fall another percentage point that sensitivity would rise to £1.4million. Sadly, this is what has happened to many pension funds since then. A year after the Friends Provident transaction, when asked why more pension funds had not adopted this new approach, Aslet said the idea of derivatives may be a stumbling block for some companies: “Our in-house expertise on derivatives and our asset management business helped to convince the trustees that we knew what we were doing”. If that psychological barrier could be overcome, he thought the same structure could be used by any company with a large pension fund.

What is strange is that, in 1968, Fosbury’s technique looked weird and new. People were cautious. But Fosbury’s innovation and guts to pursue it paid off for him, and for the early adopters that came after him, in the form of Olympic medals. Anyone watching the London Olympic 2012 would have thought it weird to see anyone attempt the high jump without using the Fosbury Flop. Watch the clip from the London 2012 Olympic Games Men’s High Jump Final, 7th August 2012. Ivan Ukhov (Russian Federation) wins the gold medal with a 2.38m High Jump. Erik Kynard (United States) takes silver with 2.33m. Mutaz Essa Barshim (Qatar), and Robert Grabarz (Great Britain), have a three-way tie for bronze at a height of 2.29m. They all use the Fosbury Flop.

Athletics Men’s High Jump Final – London 2012 Olympic Games Highlights

Similarly, in 2012, the LDI technique has become widely adopted with over 600 LDI mandates representing over £300 billion of LDI assets (source KPMG 2012). Despite the general appetite to reduce risk in pension funds, many made the call that real yields couldn’t fall any lower. Sadly they did. However, this represents a small proportion of UK pension fund liabilities. Pension funds will consider a buy-in or buy-out where the principal risk management tool used by the insurance company is LDI, but will often not consider LDI as part of their pension fund asset allocation and risk management framework. Why? Is it because they are still wary of the still relatively new LDI technique, or is it a belief that rates will mean-revert to higher levels?

Mexico 1968 Citius! Fortius!

Fosbury’s new Olympic record took its place in an Olympic Games that saw many new world and Olympic records: indeed, in the long jump, America’s Bob Beamon jumped an incredible 8.90m, a record that went on to stand for 22 years! His compatriot James Hines was the first man to run 100 metres in under 10 seconds (9.9). Tommie Smith, broke the men’s 200 metres world record (19.8 seconds); Lee Evans, that of the 400 metres (43.8 seconds); and Britain’s David Hemery that of the 400 metres hurdles with 48.1 seconds!

Tired of the mundane? Be part of ‘The Fan Dance’: the ultimate SAS fitness challenge in the stunning Brecon Beacons on Saturday 19th January 2013.

Tired of the mundane? Be part of ‘The Fan Dance’: the ultimate SAS fitness challenge in the stunning Brecon Beacons on Saturday 19th January 2013.

A good friend of mine, Peter O’Donogue and his friend, Ken Jones, are organinsing an awesome challenge for 2013 – the “Fan Dance”

If you love the rugged British countryside, breath taking scenery and the amazing sensation of your body working hard you will not want to miss the ‘Fan Dance’. For the first time ever, ex-SAS soldiers are giving you the opportunity to compete in a race along the mountainous 24km route of a genuine test they have to pass on the Special Forces Selection course.

The event takes its name from ‘Pen-Y-Fan’, the highest peak in the Brecon Beacons National Park, which competitors will have to cross not once but twice during this unforgettable experience.

This event is not only for super fit athletes and fell runners. Simply finishing the event is a huge achievement and all entrants will be rewarded with a finisher’s medal and goody bag. There is no time limit and each person is only competing against themselves, meaning all can walk away with a huge sense of pride and achievement after participating.

All ages are welcome and you can take part as a sponsored runner for your favourite charity or cause.

Be sure to not miss this unique opportunity, visit the website for more information and register early as interest is huge.

Twitter: @AvalancheEvents

Facebook: Avalanche Endurance Events

Or, if you’re leaping off the Shard, perhaps it won’t.

On September 3rd this year I’ll be taking part in TheLeap, a challenge involving abseiling at high speeds down the newly opened Shard, the highest building in Europe, in the style of a Royal Marine. This is the second in a series of Commando missions organised by the charity CommandoSpirit, which invites high flying business types (their words not mine) to move way outside their comfort zones, and push themselves to the very limits, while raising money for the RoyalMarinesCharitableTrustFund. The RMCTF supports Royal Marines, ex-Marines, and their families after injury, trauma and death. Sometimes the support this charity provides is helping marines recover from physical injuries and trauma, while sometimes it’s financial aid for the families of those who die in active service. Either way, this is a charity that helps those who put their lives on the line for us. A pretty good cause, by all accounts.

Last year, I completed theDunker, another of the Commando missions involving the underwater escape from a simulation of a helicopter crash at sea. It may have been out of pity or as a contingent funeral fund, but my friends, colleagues and family helped me surpass my £10k target and raise an admirable £11,000. This year, I’ve set myself the lofty goal of raising £25,000 by doing TheLeap.

There’s something fascinating about the extreme physical and psychological capabilities of men; where are our limits? And what happens if we push them? Not many of us ever get the opportunity to really test our own, but here’s a man who has: PeteGossis an ex-marine, world-renowned sailor, and general limit-pusher. He’s probably best known for his impromptu detour from a solo round-the-world yacht race in 1996, in which he turned his vessel around and sailed it back into the eye of the storm to rescue a fellow sailor. And in 2008 he built a woodenlugger with no modern communication or navigation tools, and sailed it to Australia in celebration of the seven Cornishmen who made the same voyage 154 years ago. His heroism doesn’t cease at the physical, though.

Even considering the clear danger of appearing close enough to Pete for comparison, I asked him to help me fundraise for The Leap by speaking publicly about his adventures. I’m humbled that he accepted and I’m delighted to announce that he will be the keynote speaker at an extraordinary, one-time event on Thursday August 30th at Pinsent Masons’ offices in London.

Please support me (and my Leap) directly, by visiting http://www.justgiving.com/rob-gardner6

and donating generously to help me raise £25,000!

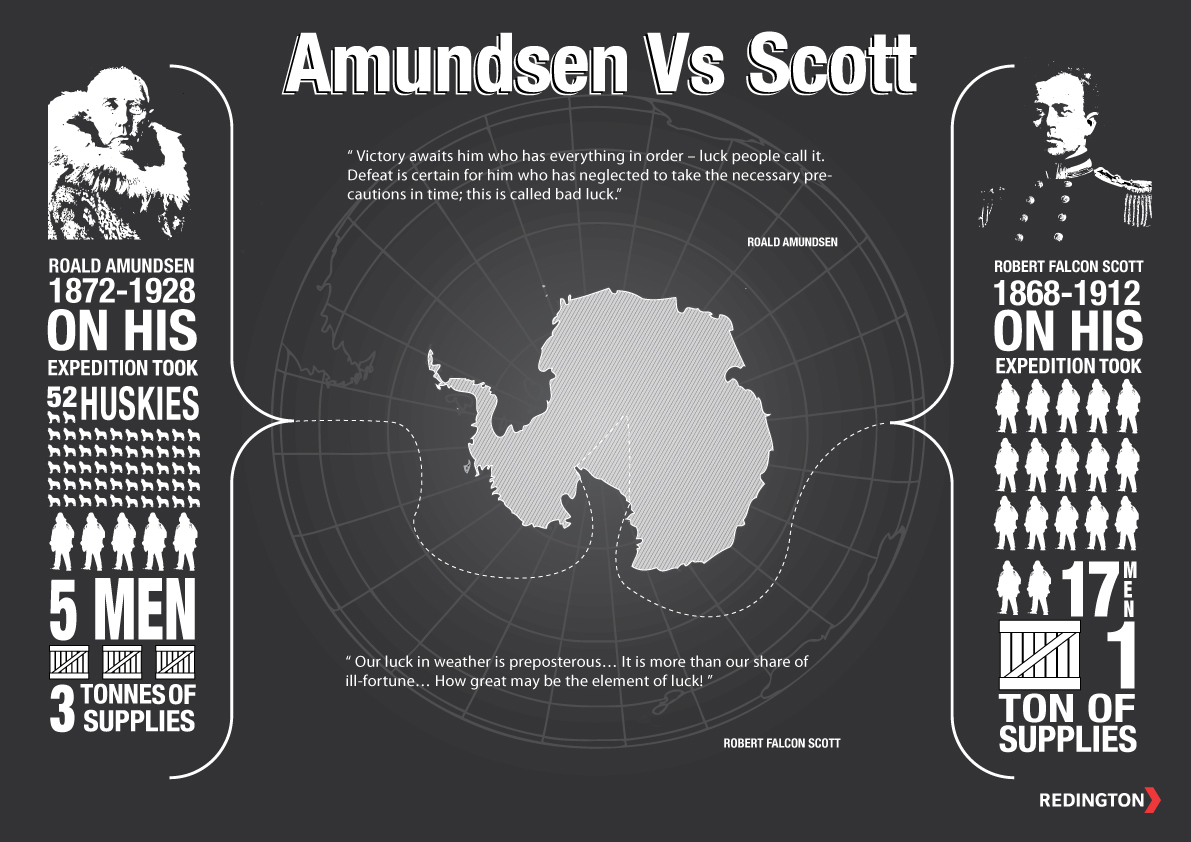

In 1911 two men began ambitious expeditions to the South Pole. Despite facing similar conditions during their 1,400 mile journeys, Roald Amundsen secured victory for his team while Robert Falcon Scott and his team suffered defeat and untimely death.

In 1911 two men began ambitious expeditions to the South Pole. Despite facing similar conditions during their 1,400 mile journeys, Roald Amundsen secured victory for his team while Robert Falcon Scott and his team suffered defeat and untimely death.

Both men and their teams contended with hostile conditions: freezing temperatures, gale force winds, fierce terrain and no safety nets. Both teams were thousands of miles from help, and without any access to communication. The conditions may have been similar; the two teams’ outcomes were not. Ultra-low gilt yields, Eurozone and regulatory headwinds, Middle Eastern hostilities and lack of sustainable economic solutions mean that pension schemes face a similarly uncertain and unknown climate.

What lessons can we draw from the past to facilitate pension schemes’ success in this new world? How can they create a more certain outcome in an uncertain economic environment?

1. Preparation

Amundsen did not take the task lightly. He spent months training with Eskimos in order to learn key survival skills in the run up to the expedition. He studied the conditions and mapped out the risks. As a result of this research, he began his journey at the Bay of Whales, reducing the distance by 60 miles. He also chose to use dogs instead of modern equipment, knowing that dogs were proven on this terrain (and would be useful as food, if needed!). Given the danger of extreme cold, Amundsen carried four thermometers in case any were broken.

Scott, meanwhile, simply repeated the route of his previous attempt in 1907 with Edmund Shackleton; he started his expedition from the usual spot, McMurdo Sound, and therefore travelled further and tackled tougher terrain. He brought motorised sleds which soon broke as they had never been tested in Polar conditions, and ponies that soon died. Scott was equipped with just one thermometer, which broke shortly into his journey, thus rendering his team ignorant of rapid falls in temperature.

Lessons for Pensions – Following in the footsteps of the successful Amundsen team, a robust Pension Risk Management Framework should be adopted before the journey (to full funding) begins. This involves knowing and quantifying, as much as possible, risks on both the asset and liability side of the pension scheme. Trustees can then map a clear path to meet their ‘Endgame’ strategy whilst minimising the risk placed on the scheme, its members and sponsor.

2. Discipline

Amundsen knew exactly how much distance needed to be covered to complete the journey on schedule. He focused his team on travelling between 15 and 20 miles each day, ignoring calls to cover more ground when the weather was fine and to bunker down when the going got tough. “It has been an unpleasant day – storm, drift, and frostbite, but we have advanced 13 miles closer to our goal,” he remarked in his journal. Even when they were within 45 miles of their target and enjoyed pleasant conditions, Amundsen stuck to the plan and travelled just 17 miles. His discipline paid off as the winning team reached the South Pole on 14th December 1911 having averaged 15.5 miles per day! And arriving safely back on the 25th January 1912 as he planned to from the outset.

Scott’s team reached the South Pole on 17th January 1912 but all died on the way back . They lacked the discipline of their rivals, exhausting themselves when the weather was clear and sitting in their tents when conditions were unpleasant. Some days they travelled 45 miles, on others zero. “I doubt if any party could travel in such weather,” Scott wrote in his infamous diary. It was not so much the conditions as exhaustion and hunger to blame for the defeat.

Lessons for Pensions – For many underfunded schemes, a return to 100% funded status in the next couple of years is unlikely. Instead, a realistic target date should be set with asset allocation based on even-more-realistic return assumptions and clearly articulated risk budgets. Should investment returns turn out better than assumed, trustees should not be afraid to ‘bank’ the excess return by allocating to lower risk/lower return assets. De-risking may provide a self-imposed discomfort in the short-term but, in the long-run, it may prove crucial to the survival of both pension scheme and sponsor.

3. Paranoia

Amundsen did not leave anything to chance. His healthy paranoia meant that his team carried enough food to survive missing a few supply depots. They also placed black stones for a kilometre around the depot, just in case weather conditions threw them off course. This combination of preparation, discipline and paranoia were key to Amundsen’s success.

Scott’s team died, tired and hungry, on the way back within a short distance of a supply depot. Despite taking three times as many men as Amundsen, this group carried one-third the amount of food – not enough to miss even a single supply depot.

Lessons for Pensions – Plan for the best, prepare for the worst. Unknown unknowns are difficult to predict and protect against; however, thanks to advances in financial modelling and quantitative analysis, we can turn some of these into known unknowns. Schemes should stress-test their portfolios against extreme scenarios before any of these scenarios arise. It is far easier to escape the herd before the herd starts stampeding! Moreover, given tighter regulations and plans for central clearing, schemes must carry enough liquid, ‘safe’ assets not only to pay members’ benefits but also to meet collateral and margin requirements.

As Amundsen remarked:

“Victory awaits him who has everything in order – luck people call it.

Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time; this is called bad luck.”

So, are you an Amundsen or a Scott?